Originally published on Medium.

Let’s start by setting the record straight. I’m no medical professional and I don’t intend on making you believe otherwise. What I’m about to share is based on my personal experience, but while I am indeed convinced that I’m special (thanks mom!), I also think that anyone who’s dealing with imposter syndrome could learn something about it today.

Before we start, I’d like to ask you something. It’s random, I’ll be the first to admit, but bear with me. While reading this article I’d like to ask you not to think of an elephant.

Let’s talk framing

Framing has been one of the most important aspects of my life since I’ve first discovered it about 15 years ago as I was dabbling in some of the early online dating communities. Granted, as a culturally-limited, skimpy, and rather lost 18-year-old I used framing for completely different purposes. But that’s a story for another day.

As I continued my self-development, I stumbled upon other people who were using framing as a tool — Gary Vaynerchuk, Trevor Moawad, and a set of stoic philosophers that I’ve learned from through Ryan Holiday. These people opened my eyes to what framing really is and how it can help you beyond getting you laid.

So here it goes. Framing is how you interpret any given situation, from daily mundane pursuits to big challenges at work. I find framing to be the most powerful tool that I’ve got, and I’m not saying this lightly.

I know what you’re thinking. Am I about to tell you that everything in life can be turned into a positive? I thought about it. I might or might not have even written a short rant on the topic before I realised it wouldn’t be much help to you.

Yes, technically, everything in life can be turned into a positive, however minimal. But it’s not so much about turning everything into a positive, as it is about thinking differently about some aspects of life.

- “I have to go to work today.” turns into “I get to go to work today.” — many people don’t have jobs, and we all know how it feels to be unemployed. How great is it that you get to put your skills to use?

- “My kids are just wild menaces.” turns into “I’ve got two beautiful children who love me and who I get to take care of and bring up.” — plenty of people want children but can’t get them, or can’t afford them, or don’t have a partner to try with.

- “My mom and I fight all the time. She’s so controlling.” turns into “My mom is still alive and I get to spend time with her.” How fortunate are you that your parents made it so far, and that you can spend time with them? Some of us are not as lucky.

You get the point. Framing is how you can put a positive spin on a negative situation. Got it? Good.

Now what does this have to do with imposter syndrome? Am I going to tell you that spinning the imposter syndrome into something positive is the cure to it all? Not really, and trust me, I’ve tried. It doesn’t work.

I also won’t tell you to ignore it, move forward, do your best, and that one day it will go away. That’s just plain dumb advice. How are you doing about that elephant that I’ve asked you not to think about? Annoying, right? Throughout reading all of this, it’s been up there, in your brain, lingering. In his book, Don’t think of an elephant, George Lakoff shows how negating a frame strengthens the frame. In other words, if I ask you not to think of an elephant, you can’t help but think of one. So if I tell you to ignore your imposter syndrome and plough through, that will only make you think about it more. Not good.

So what am I recommending?

My solution for imposter syndrome is not to push it away, or quiet it down, or find ways to get rid of it. My solution is to seek it. I know it’s not the answer you came here looking for, but I did warn you — today we’re thinking differently.

About 20 years ago Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (I can never spell his name correctly without looking it up) wrote a phenomenal book called ‘Flow.’

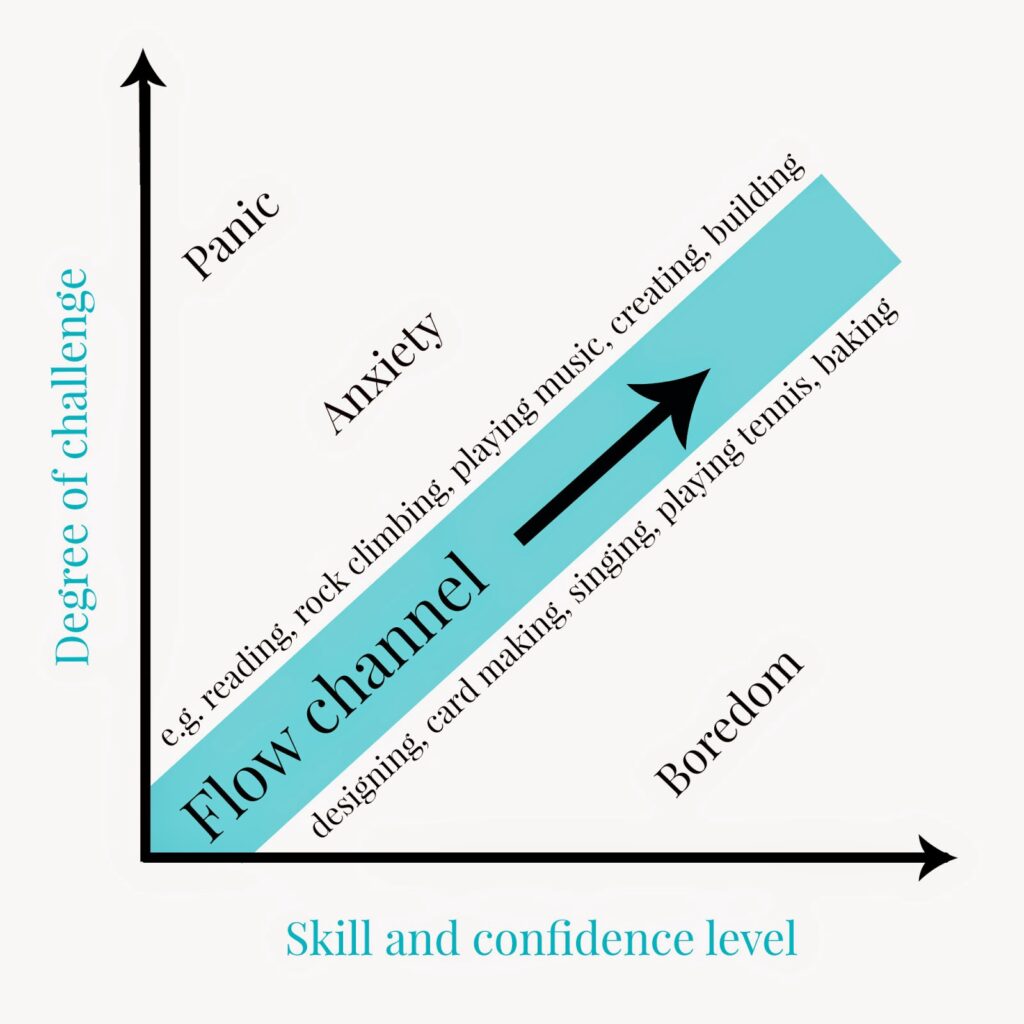

Chart of how to achieve the state of flow.

He argues that to be in a state of flow, your challenges have to be slightly outmatching your skills; to always keep you on your toes a little.

Remember how stressed you were when you drove a car for the first time? I bet that now you drive to work without even thinking about it. If anything, it’s even a little boring. That’s because as soon as a challenge gets too easy, boredom is soon to follow.

On the other hand, if I were to give you a task that’s way too complex compared to your skillset — say throw you in a room together with a bunch of NASA engineers and ask you to help them design a satellite — you’d panic.

The optimal experience is when you work on a task that’s just enough to keep you on your toes, to challenge you.It’s not too much and it’s not too little. It’s just enough.

Reading Flow has helped me make a connection — looking back, I always felt the imposter syndrome when I was slightly challenged in whatever I was doing. I never felt it when I was way in over my head, and I never felt it when I was bored. The imposter syndrome only appeared for me when I was in a state of flow, slightly challenged, hence unsure of whether I can perform a given task to the expected level. The imposter syndrome, without me understanding it, has always been a sign that I’m doing something that challenges me and that feels uncomfortable.

Let’s go back to the examples above. If I were to ask you, a driver with 20 years of experience, to give me a ride to the airport, is there any way whatsoever you’d feel like an imposter shifting gears? Absolutely not.

If I were to ask you to design the satellite, is there any way that you’d be feeling the imposter syndrome? Also no; you consciously know that you don’t belong there. It’s not a matter of feeling like a fraud. You ARE a fraud and everyone in the room will find out as soon as they’ll ask you if you think it’s best to design the new satellite based on the CALIPSO or the OCO-2. After three minutes in that room you’d start to feel apathy and will become passive, since it’s crushingly clear you haven’t got what it takes.

The only time you can feel the imposter syndrome is when you are slightly challenged. It’s a pre-cursor (and perhaps a necessary step) to growth.

That’s where framing comes in. Adjusting your vocabulary is so important, because the results you’re looking for follow your way of thinking.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” — William Shakespeare

You can choose to look at the imposter syndrome as an obstacle; something unfair your brain does that holds you back. Or you can flip the story. The imposter syndrome, whenever it appears, is a sign. It’s telling you that you’re faced with just the right challenge. If the task in front of you, or the job you’re holding, would be too much to handle, we’ve already established that you’d never doubt yourself, but rather lose motivation fast and switch off.

You can be deflated when that imposter syndrome appears, or you can see it as a voice telling you that you’re in line for some learning —whether that’s that project at work, not feeling worthy of your partner, or that you’re out of depth when you’re looking out for the kids on your own.

Change the frame. Imposter syndrome is not something to avoid; it’s something to seek. The moment you stare it in the eyes, it’s going to lose its power, and it’s going to pave the way for growth.